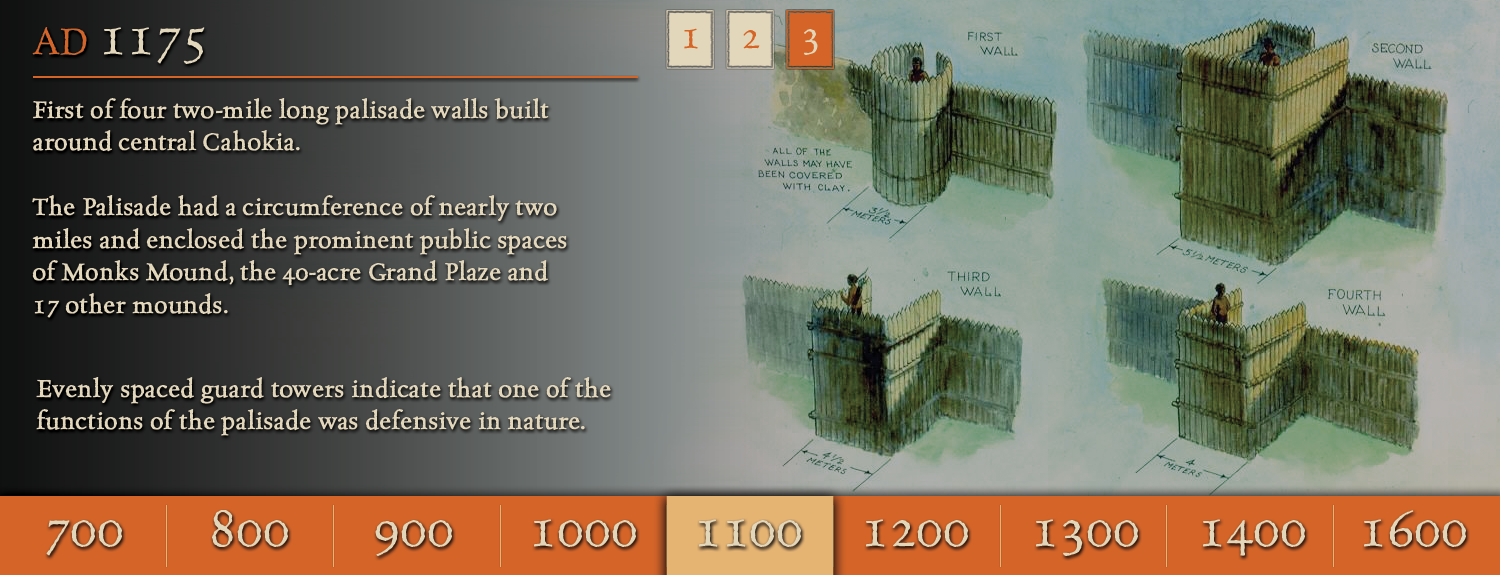

Excavations begun in 1966 eventually confirmed that an enormous, two-mile-long stockade surrounded the central portion of Cahokia. The wall appears to have been started aroundA.D. 1100 and then rebuilt three times over a period of 200 years. Each construction required 15,000-20,000 oak and hickory logs, one foot in diameter and twenty feet tall. The logs were sunk into a trench four to five feet deep and were likely supported with horizontal poles or interwoven with saplings. The stockade walls may have been covered with clay, as well, to protect them from fire and moisture.

Because there is no evidence of invasion at Cahokia some people question the purpose of the Stockade. To a degree, it probably served as a social barrier; however, three things lead most archaeologists to believe that it was primarily a defensive structure: the great height of the wall; the presence of evenly spaced bastions, projections from which archers could shoot arrows; and evidence that portions of the wall were hurriedly built, cutting through residential areas, as if danger was imminent.