A few days after crossing the stage at spring commencement, University of Missouri–St. Louis graduate Tony Farace climbs a long staircase to the top of Monks Mound near Collinsville, Ill. Once the sacred hub of a Native American empire, the vast earthwork remains at the center of efforts to understand the region’s ancient residents.

“We’re lucky to be up here,” the UMSL anthropology alumnus says of the mound, constructed roughly a millennium ago. “At that time, it was probably just the chief and maybe his closest advisors.”

The grounds of the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, dotted with more than 120 mounds dating from about 900 to 1400 A.D., are familiar yet still mysterious to Farace. Cahokia’s clues to the past have been a focus of his research since transferring to UMSL from St. Charles Community College three years ago and switching his major to anthropology.

“There’s a lot more potential in Cahokia and the surrounding area,” Farace says. “The scientific aspect has been a really interesting thing. Archeology really encompasses a lot of different fields into it. There’s a lot of chemical analysis, carbon dating – you can also look at pottery.”

His latest inquiry does just that, exploring Cahokia’s influence on pottery west of the Mississippi River. The research earned him a first-place poster presentation award at UMSL’s annual Undergraduate Research Symposium on May 1.

“The focus of my recent project was pottery from six sites that go up the Missouri River,” Farace says. “I looked at the temper, finishing surfaces and also the slips that are in Cahokian pottery, and I related them to those six sites across the Mississippi.

“Pottery in the Mississippian era is about style and technique,” he adds. “The temper is what they used to help fire the clay and help it keep its shape, and they would also use slip, which is clay mixed in water, and they would add colors to it, like red or black. They would use different finishing techniques – some people around here used a smooth finishing technique, and others would use a cord-marking technique.”

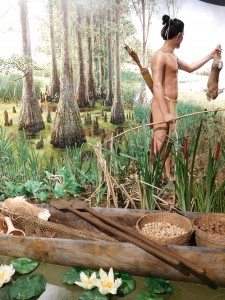

In addition to stylistic hints about where and what the people of Cahokia were trading hundreds of years ago, studying the pieces of pottery provides a sense of what these early inhabitants were eating and carrying.

“You can take a sample of the inside to look at different isotopes of either nitrogen or carbon,” Farace says. “These isotopes can show you what kind of animal proteins or plant remains were in the pots.”

Farace’s own study confirmed his hypothesis that the closer the proximity of an early Mississippian pottery artifact to Cahokia Mounds, the stronger the stylistic influences.

“There aren’t that many sites excavated in Missouri, so the six sites are a small view of an even smaller view,” Farace says. “It’s not really been done before, and the results aren’t perfect, but hopefully they’re a good base for anyone who wants to go on later and do more.”

This fall, Farace will continue his education as a graduate student at Southern Illinois University – and probably his research on the pottery of Cahokia, too. He compares what he plans to investigate with what other archeologists have learned from studying lithics, such as arrowheads.

“They can look at these different arrowheads and pinpoint who actually made them, because the technique is so distinctive,” Farace says. “So I’m hoping to try to do that with pottery: look at different styles and see where they originate and also just compare the region overall, trying to see where they traded and what economic changes they had.”

During his time as a UMSL anthropology student, Farace has worked on several excavation sites throughout the region, ranging from St. Charles, Mo., to East St. Louis, Ill. Last fall, he completed an internship with the Illinois State Archaeological Society, and this summer he is a teaching assistant at a UMSL field school in Excelsior Springs, Mo.

“We teach students to first survey an area without digging and then how to dig and excavate, how to do leveling and just how systematic it is,” he says.

Standing atop Monks Mound, Farace remarks on the impressive view, adding offhand that evidence suggest the chief’s house was struck by lightning. Then he points at an area on the lower terrace of the mound, describing it as similar to a court or civic center.

“They used to play ‘chunkey,’” he says. “They had these stones, round on the side and flat in the middle, and they would have one person roll it on the ground. Then people would try to land spears where the chunkey landed. It was kind of an ancient form of curling.”

Many questions remain, including why the early urban residents of the region eventually left.

“There’s a few theories, but one just came out a little bit ago that sounds more probable than the rest,” Farace says. “There’s new evidence of a flood that might’ve taken out this area around 1200 A.D. It would have just flooded this whole area – not a lot, but enough that you couldn’t live here.”